By Katie Kerwin McCrimmon

Justin Swanstrom used to be set for life.

The 56-year-old Denver lawyer and his partner owned a loft in the trendy Ballpark neighborhood downtown. And Swanstrom had a rental home that provided extra income.

Then, last January, he lost his job and two months later, had a heart attack that landed him in St. Joseph Hospital with massive bills and no health insurance.

“I received excellent care. I just feel guilty that I couldn’t pay them,” Swanstrom said.

He and his partner had to sell the loft. Swanstrom lost the rental to foreclosure. And, he’s subsisting now on $700 on month in unemployment, unable to find work and barely able to contribute his share of the rent, much less make a dent in his bills.

The medical debt has wrecked Swanstrom’s financial reputation and he’s now hunting for jobs far beneath his education level.

“Nobody is going to hire me with a bad credit rating. I look like a deadbeat,” Swanstrom said.

A new bill in Colorado, SB 12-134, has passed both houses and is expected to receive the governor’s signature. It requires Colorado hospitals to help uninsured and people like Swanstrom by automatically billing them at the lowest-negotiated fee for their medical care. People without insurance often pay much higher costs for health care than those with health insurance. Billing discrimination has meant that people who suffer a single health calamity can face a lifetime of financial ruin.

“The goal of the Hospital Payment Assistance Program is to provide a way for hard-working, uninsured Coloradans to responsibly pay a fair price for their medical care,” said the bill’s sponsor, Sen. Irene Aguilar, D-Denver, who is also an internal medicine doctor at Denver Health. “And equally importantly, the bill calls for steps to ensure that all Coloradans know this program exists so that they don’t endanger their health and livelihood out of fear of bankruptcy.”

Hospitals have so-called “sticker prices” for every procedure and supply item. Insurance companies never pay full price, but individuals without insurance often get stuck being billed the sticker price or higher. Aguilar said that in Colorado costs for uninsured people can soar to as high as 495 percent of the cost for hospital services and 842 percent of the cost for outpatient procedures. In other words, low-income and uninsured people who are least able to afford expensive health care often are billed the highest rates.

The Colorado Hospital Association supported Aguilar’s bill after she agreed to lower the threshold for participating from 400 percent of the federal poverty level (about $92,000 a year for a family of four) to 250 percent (about $56,000 for a family of four). Hospitals are already supposed to publish guidelines for offering charity care to the poorest patients. But few consumers without adequate insurance know their rights and often end up saddled with massive health debt.

SB 12-134 requires hospitals to be transparent about their financial assistance and charity programs by posting them in hospital waiting rooms and printing the policies on bills. They also must screen the uninsured for discount programs, limit charges to the hospitals’ lowest negotiated private payer price, offer reasonable payment plans, and ensure that patients have received payment options before their bills are sent to collections.

Advocates with the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, a consortium of 50 health organizations and 500,000 consumer members, pushed for passage of the bill.

“Nobody wants to end up in this situation,” said Serena Woods, director of strategic engagement for the CCHI. “Because uninsured Coloradans lack the bargaining power of insurance companies, they are charged, twice, three times, even four times as much as their insured neighbors.”

Justin Swanstrom suffered chest pains for two days, tried to ignore the pain and went to a chiropractor before his partner tricked him into going to the ER. Once there, doctors hooked Swanstrom to monitors, found he was having a heart attack and wheeled him directly into surgery.

Paramedics have told Aguilar of other cases where people suffering heart attacks and other health emergencies refused medical care because they didn’t want to destroy their families’ finances.

“You shouldn’t have to worry about going bankrupt. You should take care of your health and do the right thing. If you need to go to the hospital, you should go,” Aguilar said.

Each hospital system has a different policy. Many for-profit hospitals require patients to agree to pay up front before they receive treatment.

That type of policy can blindside people, even those who think they have good health insurance.

Leadville teacher Heidi Johnson, 33, was snowboarding at Loveland a month ago and blew out her knee.

Ski patrol workers helped her down the mountain and she received emergency care at Centura’s Keystone Medical Clinic. Days later, on the morning that Johnson was supposed to have surgery at the Vail Valley Surgery Center, she said she received a call telling her that she would have to agree to pay $2,750 up front or she wouldn’t get the surgery. The center is partially owned, but not operated by the Vail Valley Medical Center.

“What are you talking about?” Johnson remembers saying. “But it was right before I went in. They said, ‘This is what you have to pay. The best we can do is give you four payments.’

“What am I going to do? I needed the surgery. I can’t walk. I figured I have to do this now. I’ll figure this out. I’ll just have to take it out of savings,” Johnson said.

Feeling she had no choice, Johnson signed the paper and received surgery for two torn ligaments in her left knee, her anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and her lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

After the surgery, as she began to recover, Johnson realized that she was facing a financial mess.

“I’m looking at all of these bills and I can’t afford that. I’m out of work for the next month and now I have to pay for physical therapy three or four times a week,” she said. “I thought teachers are supposed to have good health insurance.”

Instead, she learned that her policy has a $1,000 deductible and that she’ll have to pay at least $3,750 out of pocket because her insurance covers 80 percent of her expenses while she has to cover 20 percent.

She’s trying to go to physical therapy and heal as quickly as possible, but each time she goes, she has to a pay a $37 co-pay, which can add up to hundreds of dollars a month.

Johnson called the surgery center back and tried to negotiate a better deal. She hoped to make smaller payments.

“I was under the impression that if you paid at least $10 a month, you could do that,” Johnson said.

But, she said the billing department told her that she signed the financial agreement and would have to abide by it or they’d turn her over to debt collectors. Knowing she wouldn’t have enough to cover payments to the clinic, Johnson canceled the debit card she had given to the surgery center on the morning of her procedure. The new law focuses on people who are uninsured, not those who are underinsured like Johnson. But many hospitals have charity policies and sometimes negotiate with patients who are having trouble paying for care. For now, Johnson is trying to heal and plans to sort out bills later.

On top of getting better financial advice about surgery, Johnson thinks consumers need more help understanding health insurance.

“I just wish I got more explanation on the insurance (through my work). I had two choices. Maybe I chose the wrong one.”

Altogether, Johnson thinks she’s facing about $4,000 in medical bills. Since she can’t walk, she can’t teach. She says she’s missing herfifth-graders and doesn’t know if she’ll be able to wait tables this summer to supplement her income.

“It’s terrible. This isn’t what I want to be doing. I want to be teaching and hiking, running and biking,” she said.

Shewit Doherty is still paying off medical bills from a snowboarding accident three years ago. She was 19, uninsured and a student at the University of Denver when she broke her wrist while snowboarding at Arapahoe Basin in 2009. She went for help to the Keystone Medical Clinic.

“I told them I didn’t have insurance. They said that in order to be seen, I had to put down $400 up front,” Doherty said. “When you’re in pain like that, you’ll say yes to anything. I put in on my credit card and had to agree to accept the bill later.”

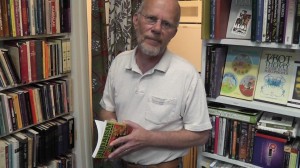

Justin Swanstrom was sure he was going to die when he suffered a heart attack two months after losing his job. As he had surgery, he repeated prayers. Now he helps in his partner’s book store, but can’t find work and still faces thousands of dollars in medical bills.

A bill for a couple thousand dollars did arrive later. Doherty had heard that if you offer to pay cash up front, hospitals would sometimes negotiate a smaller fee. But, she said they refused and never offered her any sort of payment plan.

“I was really amazed that even after we enquired (about charity care or negotiated rates) information was not given up front to me. The bill now is requiring that they do make it readily available and inform the consumer. It felt like they didn’t want you to know there was another option,” Doherty said.

The full-time student, who only had part-time work, has been paying off her bill a few dollars at a time. Now 21 and preparing for a study abroad program in Argentina, she’s just about to make her last payment.

“I haven’t neglected the bill,” she said. “It’s not that we don’t want to pay. But if it’s not reasonable or affordable, it’s not going to happen.”

When Justin Swanstrom was having his heart attack, he was sure he was going to die. He lay on the surgery table repeating Jewish prayers, assuming his life had ended.

He survived only to find that he was facing $60,000 in medical bills and wouldn’t even have enough money to buy the Lipitor he’s supposed to take for high cholesterol. Finally after nearly a year of negotiating, the hospital has reduced his charges to about $4,000.

Swanstrom is continuing his job search and works occasionally at his partner’s Denver bookstore. Full of mystical books and spiritual symbols, it’s a peaceful place.

Even so, after losing so much over the past year, Swanstrom has to think hard about advice he would give to a friend who needed to go to the hospital, but didn’t have insurance.

“Don’t go,” he says, only half kidding. “It’s going to be much worse than you expect.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story said that the Steadman Clinic in Vail told Heidi Johnson that she had to pay in advance before receiving surgery. That was incorrect. While Dr. Robert LaPrade of the Steadman Clinic performed Johnson’s surgery, the procedure took place at the Vail Valley Surgery Center. That was the entity that requested payment from Johnson.